How did Forest Rules Affect Cultivation?

Enroll to start learning

You’ve not yet enrolled in this course. Please enroll for free to listen to audio lessons, classroom podcasts and take practice test.

Interactive Audio Lesson

Listen to a student-teacher conversation explaining the topic in a relatable way.

Introduction to Shifting Cultivation

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Today, we'll discuss shifting cultivation, also known as swidden agriculture. Can anyone tell me what they think it involves?

Isn’t it when farmers cut and burn forest areas to grow their crops?

Exactly! This method has been practiced in many parts of the world. In India, there are various local terms for it, such as jhum and bewar. It typically involves growing multiple crops in a small area.

Why do they burn the forest before planting?

Great question! Burning provides nutrients from the ash, benefiting the soil for cultivation. However, it also requires leaving the land fallow for many years to allow regeneration.

But how did colonialism affect this practice?

Under colonial rule, the perspective shifted. Governments saw it as unproductive and harmful to forests. This led to serious restrictions on these traditional practices.

So, what happened to the communities that depended on this method?

They faced forced displacement and had to adapt to new rules, sometimes leading to resistance or rebellion against colonial authorities.

In summary, shifting cultivation was a sustainable practice that faced drastic changes during colonial times, fundamentally affecting communities reliant on this method.

The Impact of Colonial Forest Policies

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Let’s talk about the specific forest policies enacted by colonial powers. How were these perceived by the local people?

They likely saw them as unfair or harmful to their lifestyles.

Exactly! The colonial authorities viewed forests as land to be 'improved' economically, which often confused the ecological importance of these areas. They classified and restricted access to forests, often labeling local agricultural methods as detrimental.

Did this lead to any resistance from the communities?

Yes, it did! Many communities resisted through both organized rebellions and everyday acts of defiance against colonial laws.

So, what were the long-term effects on these communities?

The loss of traditional agricultural practices led many communities to change occupations, diminishing their cultural heritage and dependence on local ecosystems.

In summary, the colonial forest policies disrupted established agricultural practices, causing significant cultural and socio-economic impacts on indigenous communities.

The Role of Resistance and Adaptation

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Now, let’s explore how communities resisted these changes brought on by colonial forest rules. How do you think they responded?

They might have fought back or tried to keep their practices alive?

Absolutely! Many groups started rebellions, and their struggles often highlighted the injustices imposed by colonial policies. In many instances, these resistances were deeply tied to their identities as forest dwellers.

Were there successful rebellions, then?

Some were successful in temporarily halting colonial practices, but most often they faced severe backlash from colonial forces.

Did any communities adapt the way they farmed?

Yes, adaptation did occur. Some communities began to utilize different farming methods allowed by the new laws but at the expense of biodiversity.

In summary, communities showed resilience, adapting where necessary and resisting oppression when possible, as they navigated the challenges imposed by colonial changes.

Introduction & Overview

Read summaries of the section's main ideas at different levels of detail.

Quick Overview

Standard

The section examines the effects of colonial forest rules on shifting cultivation practices, highlighting how practices such as burning forests for agriculture were curtailed. It discusses the changes in agricultural practices, leading to displacement and hardship for communities that relied on these traditional methods.

Detailed

Detailed Summary

This section discusses the significant impact of European colonial rules on shifting cultivation practices, also known as swidden agriculture, prevalent in various global regions including Asia, Africa, and South America. The indigenous agricultural system involves cutting and burning parts of the forest to cultivate crops on nutrient-rich ash before allowing the land to lie fallow for extensive periods, allowing the forest to regenerate. However, colonial powers viewed such practices as detrimental to forest conservation and economic viability. Consequently, colonial regimes prohibited shifting cultivation, culminating in the forced dislocation of forest-dwelling communities and altering their traditional lifestyles.

The colonial perspective considered forests as unproductive land, disregarding the ecological significance of maintaining biodiversity and indigenous farming techniques. This led to a systematic replacement of local agricultural practices with more commercial, monoculture plantations, disrupting the socio-economic fabric of forest communities. Many communities were compelled to resist the changes through rebellion and adaptation, underscoring the complex interaction between colonial policies and forest-based livelihoods.

Youtube Videos

Audio Book

Dive deep into the subject with an immersive audiobook experience.

Introduction to Shifting Cultivation

Chapter 1 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

One of the major impacts of European colonialism was on the practice of shifting cultivation or swidden agriculture. This is a traditional agricultural practice in many parts of Asia, Africa and South America. It has many local names such as lading in Southeast Asia, milpa in Central America, chitemene or tavy in Africa, and chena in Sri Lanka. In India, dhya, penda, bewar, nevad, jhum, podu, khandad and kumri are some of the local terms for swidden agriculture.

Detailed Explanation

Shifting cultivation is a farming method where farmers clear a patch of forest land, usually by cutting down and burning trees. They then plant crops in the nourished soil, using the ashes from the burned vegetation as fertilizer. This practice is common in various regions worldwide, each having its own term and slight variations in the method. In India, terms such as jhum or podu highlight this practice's local importance, adapting to different environments and communities.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine clearing a small area in your backyard to plant a vegetable patch. You clear the weeds, use the dried grass as mulch, and then plant your seeds. After a year, if the plants deplete the soil nutrients, you may move to a new spot to allow the old patch to regenerate. This is similar to what many communities do, but on a larger scale, allowing the forest to recover before returning to farm it again.

Process of Shifting Cultivation

Chapter 2 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

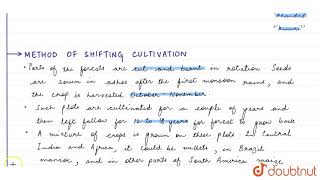

In shifting cultivation, parts of the forest are cut and burnt in rotation. Seeds are sown in the ashes after the first monsoon rains, and the crop is harvested by October-November. Such plots are cultivated for a couple of years and then left fallow for 12 to 18 years for the forest to grow back. A mixture of crops is grown on these plots. In central India and Africa it could be millets, in Brazil manioc, and in other parts of Latin America maize and beans.

Detailed Explanation

The cultivation cycle involves cutting down trees in a specific area and burning them to prepare the land. This is done just before the rains, ensuring that the nutrients from the ash will support growth. After a couple of harvest seasons, the land is left to rest for many years, allowing natural regeneration of the forest. This sustainable method helps maintain the balance of the ecosystem and supports diverse crops.

Examples & Analogies

Think of it like rotating crops in a small garden. If you plant squash in one spot for a couple of years, it may deplete the soil. So, you move to a different location and let the original area recover while growing new vegetables, making sure that over time, each part of your garden gets a chance to rest and rejuvenate.

Colonial Impact on Shifting Cultivation

Chapter 3 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

European foresters regarded this practice as harmful for the forests. They felt that land which was used for cultivation every few years could not grow trees for railway timber. When a forest was burnt, there was the added danger of the flames spreading and burning valuable timber. Shifting cultivation also made it harder for the government to calculate taxes. Therefore, the government decided to ban shifting cultivation. As a result, many communities were forcibly displaced from their homes in the forests. Some had to change occupations, while some resisted through large and small rebellions.

Detailed Explanation

Colonial authorities viewed shifting cultivation as a threat to valuable forest resources. They justified banning it by claiming it hindered timber production essential for railways and trade. This ban not only imposed restrictions on traditional farming practices but also led to the eviction of many forest-dwelling communities, disrupting their way of life. The resistance to these changes sparked various forms of rebellion among displaced peoples.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine if a new regulation forced you to stop gardening in your backyard, claiming that it's preventing a community garden project. You might feel frustrated, especially if that garden is your source of fresh vegetables. The displacement could lead you to protest or seek other ways to keep your access to fresh produce, reflecting how communities reacted against the colonial rules.

Key Concepts

-

Shifting Cultivation: A sustainable agricultural practice of rotating crops with fallow periods allowing forest regeneration.

-

Colonial Impact: The restrictions placed by colonial powers led to severe changes in traditional farming practices.

-

Displacement: Communities were often displaced due to the imposition of colonial forest laws.

Examples & Applications

In India, practices like jhum and bewar represent local names for shifting cultivation, which faced restrictions during colonial rule.

The introduction of monocultures during colonial times, such as tea and coffee plantations, exemplified the shift away from traditional mixed-crop agriculture.

Memory Aids

Interactive tools to help you remember key concepts

Rhymes

Cultivate and rotate, watch the forests thrive, shifting agri keeps the land alive.

Stories

Imagine a community in the forest. They lovingly tend to their crops and then let the land rest. With colonialism’s arrival, their practices were challenged, leading them to adapt or resist, showing their enduring spirit.

Memory Tools

P.A.R.A.D.I.G.M. - Policies Affecting Resource Access Displace Indigenous Groups' Methods.

Acronyms

S.C.A.R.E. - Shifting Cultivation Altered by Restrictions and Economic policies.

Flash Cards

Glossary

- Shifting Cultivation

An agricultural practice involving rotation of crop cultivation and fallow periods, often in forested areas.

- Swidden Agriculture

Another name for shifting cultivation, highlighting the practice of clearing land through slash-and-burn techniques.

- Colonialism

A policy by which a country establishes control over a territory and its people, often leading to cultural and economic changes.

- Monoculture

The agricultural practice of growing a single crop species over a wide area, often resulting in a loss of biodiversity.

- Displacement

The forced removal of individuals or communities from their traditional lands.

Reference links

Supplementary resources to enhance your learning experience.