Basic Structure of Computers - 1.1

Introduction & Overview

Read summaries of the section's main ideas at different levels of detail.

Quick Overview

Standard

This section provides a foundational understanding of a computer's basic structure. It begins by defining the three essential layers of a computer system: the tangible Hardware, the intangible Software (instructions), and Firmware (software permanently embedded in hardware). A historical overview traces computer evolution through five generations, highlighting shifts from vacuum tubes to transistors, integrated circuits, microprocessors, and current advancements in parallelism and AI. The three core components of any general-purpose computer—the Processor (CPU), Memory (RAM), and Input/Output (I/O) Devices—are detailed. Furthermore, the fundamental Stored Program Concept is explained, contrasting the shared bus of Von Neumann architecture with the separate instruction/data paths of Harvard architecture. The section concludes with a high-level explanation of the Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle, illustrating how the CPU processes instructions.

Detailed Summary

1.1 Basic Structure of Computers

At its core, a computer is a sophisticated electronic device meticulously designed to perform computation and data manipulation through the execution of stored instructions. Understanding its fundamental structure is the first step toward comprehending how these complex machines operate.

● Definition of a Computer System: Hardware, Software, Firmware.

A complete computer system is not merely a collection of electronic components, but a tightly integrated ecosystem where distinct layers work in concert:

1. Hardware: This refers to all the tangible, physical components that make up the computer. This includes the intricate electronic circuits, semiconductor chips (like the CPU and memory), printed circuit boards, connecting wires, power supply units, various storage devices, and all input/output (I/O) peripherals (keyboards, monitors, network cards, etc.). Hardware provides the raw computational power and the physical pathways for information.

2. Software: In contrast to hardware, software is intangible. It is the organized set of instructions, or programs, that dictates to the hardware what tasks to perform and how to execute them. Software can range from low-level commands that directly interact with hardware to complex applications that users interact with. It is loaded into memory and processed by the CPU.

3. Firmware: Positioned at the intersection of hardware and software, firmware is a special class of software permanently encoded into hardware devices, typically on Read-Only Memory (ROM) chips. It provides the essential, low-level control needed for the device's specific hardware components to function correctly, acting as an initial bridge between the raw hardware and higher-level software. A common example is the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) in personal computers, which initializes the system components when the computer starts up. Without firmware, the hardware would be inert.

● Evolution of Computers: Generations and Key Architectural Advancements.

Computer architecture has undergone profound transformations, often categorized into "generations" based on the prevailing technological breakthroughs and the resultant shifts in design paradigms and capabilities:

1. First Generation (circa 1940s-1950s - Vacuum Tubes): These pioneering computers, such as ENIAC and UNIVAC, relied on vacuum tubes for their core logic and memory. They were colossal in size, consumed immense amounts of electricity, generated considerable heat, and were notoriously unreliable. Programming was done directly in machine language or via physical wiring. The pivotal architectural advancement was the stored-program concept, which allowed programs to be loaded into memory, making computers far more flexible and programmable than previous fixed-function machines.

2. Second Generation (circa 1950s-1960s - Transistors): The invention of the transistor was revolutionary. Transistors were significantly smaller, faster, more reliable, and consumed far less power than vacuum tubes. This led to more compact, dependable, and commercially viable computers. Magnetic core memory became prevalent. Crucially, the development of high-level programming languages (like FORTRAN and COBOL) and their respective compilers began to abstract away the direct manipulation of machine code, making programming more accessible.

3. Third Generation (circa 1960s-1970s - Integrated Circuits (ICs)): The integration of multiple transistors and other electronic components onto a single silicon chip (the Integrated Circuit) marked a dramatic leap. This allowed for unprecedented miniaturization, increased processing speeds, and reduced manufacturing costs. This era saw the emergence of more sophisticated operating systems capable of multiprogramming (running multiple programs concurrently) and time-sharing, enabling shared access to powerful mainframes.

4. Fourth Generation (circa 1970s-Present - Microprocessors): The invention of the microprocessor, which integrated the entire Central Processing Unit (CPU) onto a single silicon chip, revolutionized computing. This led directly to the proliferation of personal computers, powerful workstations, and the rapid expansion of computer networking. This generation also witnessed the rise of specialized processors and the early adoption of parallel processing techniques, as designers started hitting fundamental limits in single-processor performance improvements (like clock speed).

5. Fifth Generation (Present and Beyond - Advanced Parallelism, AI, Quantum): This ongoing era focuses on highly parallel and distributed computing systems, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, natural language processing, and potentially quantum computing. Architectural advancements include multi-core processors, specialized AI accelerators, and highly complex memory hierarchies designed for massive data processing. The emphasis shifts from raw clock speed to maximizing throughput through parallel execution.

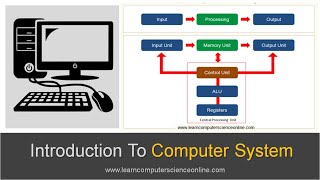

● Components of a General-Purpose Computer: While architectures vary, a general-purpose computer consistently comprises three primary and interconnected functional blocks:

1. Processor (Central Processing Unit - CPU): Often referred to as the "brain," the CPU is the active component responsible for executing all program instructions, performing arithmetic calculations (addition, subtraction), logical operations (comparisons, AND/OR/NOT), and managing the flow of data. It performs the actual "computing" work.

2. Memory (Main Memory/RAM): This acts as the computer's temporary, high-speed workspace. It holds the program instructions that the CPU is currently executing and the data that those programs are actively using. Memory is characterized by its volatility, meaning its contents are lost when the power supply is removed. It provides the CPU with rapid access to necessary information.

3. Input/Output (I/O) Devices: These components form the crucial interface between the computer and the external world. Input devices (e.g., keyboard, mouse, touchscreen, microphone) translate user actions or physical phenomena into digital signals that the computer can understand. Output devices (e.g., monitor, printer, speakers, robotic actuators) convert processed digital data from the computer into a form perceptible to humans or for controlling external machinery.

● Stored Program Concept: Von Neumann Architecture vs. Harvard Architecture.

The Stored Program Concept is the foundational principle of almost all modern computers. It dictates that both program instructions and the data that the program manipulates are stored together in the same main memory. The CPU can then fetch either instructions or data from this unified memory space. This radical idea, pioneered by John von Neumann, enables incredible flexibility: the same hardware can execute vastly different programs simply by loading new instructions into memory.

1. Von Neumann Architecture: In this model, a single common bus (a set of wires) is used for both data transfers and instruction fetches. This means that the CPU cannot fetch an instruction and read/write data simultaneously; it must alternate between the two operations. This simplicity in design and control unit logic was a major advantage in early computers. While simple, the shared bus can become a bottleneck, often referred to as the "Von Neumann bottleneck," as the CPU must wait for memory operations to complete.

2. Harvard Architecture: In contrast, the Harvard architecture features separate memory spaces and distinct buses for instructions and data. This allows the CPU to fetch an instruction and access data concurrently, potentially leading to faster execution, especially in pipelined processors where multiple stages of instruction execution can proceed in parallel. Many modern CPUs, while conceptually Von Neumann, implement a modified Harvard architecture internally by using separate instruction and data caches to achieve simultaneous access, even if the main memory is unified.

● The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle: A High-Level Overview of Program Execution.

This cycle represents the fundamental, iterative process by which a Central Processing Unit (CPU) carries out a program's instructions. It is the rhythmic heartbeat of a computer.

1. Fetch: The CPU retrieves the next instruction that needs to be executed from main memory. The address of this instruction is held in a special CPU register called the Program Counter (PC). The instruction is then loaded into another CPU register, the Instruction Register (IR). The Control Unit (CU) orchestrates this transfer.

2. Decode: The Control Unit (CU) takes the instruction currently held in the Instruction Register (IR) and interprets its meaning. It deciphers the operation code (opcode) to understand what action is required (e.g., addition, data movement, conditional jump) and identifies the operands (the data or memory addresses that the instruction will operate on).

3. Execute: The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU), guided by the Control Unit, performs the actual operation specified by the decoded instruction. This could involve an arithmetic calculation, a logical comparison, a data shift, or a control flow change (like a jump). The result of the operation is produced.

4. Store (or Write-back): The result generated during the Execute phase is written back to a designated location. This might be another CPU register for immediate use, a specific memory location, or an output device. Simultaneously, the Program Counter (PC) is updated to point to the address of the next instruction to be fetched, typically by incrementing it, or by loading a new address if the executed instruction was a branch or jump. The cycle then repeats continuously for the duration of the program.

Detailed

1.1 Basic Structure of Computers

At its core, a computer is a sophisticated electronic device meticulously designed to perform computation and data manipulation through the execution of stored instructions. Understanding its fundamental structure is the first step toward comprehending how these complex machines operate.

● Definition of a Computer System: Hardware, Software, Firmware.

A complete computer system is not merely a collection of electronic components, but a tightly integrated ecosystem where distinct layers work in concert:

1. Hardware: This refers to all the tangible, physical components that make up the computer. This includes the intricate electronic circuits, semiconductor chips (like the CPU and memory), printed circuit boards, connecting wires, power supply units, various storage devices, and all input/output (I/O) peripherals (keyboards, monitors, network cards, etc.). Hardware provides the raw computational power and the physical pathways for information.

2. Software: In contrast to hardware, software is intangible. It is the organized set of instructions, or programs, that dictates to the hardware what tasks to perform and how to execute them. Software can range from low-level commands that directly interact with hardware to complex applications that users interact with. It is loaded into memory and processed by the CPU.

3. Firmware: Positioned at the intersection of hardware and software, firmware is a special class of software permanently encoded into hardware devices, typically on Read-Only Memory (ROM) chips. It provides the essential, low-level control needed for the device's specific hardware components to function correctly, acting as an initial bridge between the raw hardware and higher-level software. A common example is the Basic Input/Output System (BIOS) in personal computers, which initializes the system components when the computer starts up. Without firmware, the hardware would be inert.

● Evolution of Computers: Generations and Key Architectural Advancements.

Computer architecture has undergone profound transformations, often categorized into "generations" based on the prevailing technological breakthroughs and the resultant shifts in design paradigms and capabilities:

1. First Generation (circa 1940s-1950s - Vacuum Tubes): These pioneering computers, such as ENIAC and UNIVAC, relied on vacuum tubes for their core logic and memory. They were colossal in size, consumed immense amounts of electricity, generated considerable heat, and were notoriously unreliable. Programming was done directly in machine language or via physical wiring. The pivotal architectural advancement was the stored-program concept, which allowed programs to be loaded into memory, making computers far more flexible and programmable than previous fixed-function machines.

2. Second Generation (circa 1950s-1960s - Transistors): The invention of the transistor was revolutionary. Transistors were significantly smaller, faster, more reliable, and consumed far less power than vacuum tubes. This led to more compact, dependable, and commercially viable computers. Magnetic core memory became prevalent. Crucially, the development of high-level programming languages (like FORTRAN and COBOL) and their respective compilers began to abstract away the direct manipulation of machine code, making programming more accessible.

3. Third Generation (circa 1960s-1970s - Integrated Circuits (ICs)): The integration of multiple transistors and other electronic components onto a single silicon chip (the Integrated Circuit) marked a dramatic leap. This allowed for unprecedented miniaturization, increased processing speeds, and reduced manufacturing costs. This era saw the emergence of more sophisticated operating systems capable of multiprogramming (running multiple programs concurrently) and time-sharing, enabling shared access to powerful mainframes.

4. Fourth Generation (circa 1970s-Present - Microprocessors): The invention of the microprocessor, which integrated the entire Central Processing Unit (CPU) onto a single silicon chip, revolutionized computing. This led directly to the proliferation of personal computers, powerful workstations, and the rapid expansion of computer networking. This generation also witnessed the rise of specialized processors and the early adoption of parallel processing techniques, as designers started hitting fundamental limits in single-processor performance improvements (like clock speed).

5. Fifth Generation (Present and Beyond - Advanced Parallelism, AI, Quantum): This ongoing era focuses on highly parallel and distributed computing systems, artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, natural language processing, and potentially quantum computing. Architectural advancements include multi-core processors, specialized AI accelerators, and highly complex memory hierarchies designed for massive data processing. The emphasis shifts from raw clock speed to maximizing throughput through parallel execution.

● Components of a General-Purpose Computer: While architectures vary, a general-purpose computer consistently comprises three primary and interconnected functional blocks:

1. Processor (Central Processing Unit - CPU): Often referred to as the "brain," the CPU is the active component responsible for executing all program instructions, performing arithmetic calculations (addition, subtraction), logical operations (comparisons, AND/OR/NOT), and managing the flow of data. It performs the actual "computing" work.

2. Memory (Main Memory/RAM): This acts as the computer's temporary, high-speed workspace. It holds the program instructions that the CPU is currently executing and the data that those programs are actively using. Memory is characterized by its volatility, meaning its contents are lost when the power supply is removed. It provides the CPU with rapid access to necessary information.

3. Input/Output (I/O) Devices: These components form the crucial interface between the computer and the external world. Input devices (e.g., keyboard, mouse, touchscreen, microphone) translate user actions or physical phenomena into digital signals that the computer can understand. Output devices (e.g., monitor, printer, speakers, robotic actuators) convert processed digital data from the computer into a form perceptible to humans or for controlling external machinery.

● Stored Program Concept: Von Neumann Architecture vs. Harvard Architecture.

The Stored Program Concept is the foundational principle of almost all modern computers. It dictates that both program instructions and the data that the program manipulates are stored together in the same main memory. The CPU can then fetch either instructions or data from this unified memory space. This radical idea, pioneered by John von Neumann, enables incredible flexibility: the same hardware can execute vastly different programs simply by loading new instructions into memory.

1. Von Neumann Architecture: In this model, a single common bus (a set of wires) is used for both data transfers and instruction fetches. This means that the CPU cannot fetch an instruction and read/write data simultaneously; it must alternate between the two operations. This simplicity in design and control unit logic was a major advantage in early computers. While simple, the shared bus can become a bottleneck, often referred to as the "Von Neumann bottleneck," as the CPU must wait for memory operations to complete.

2. Harvard Architecture: In contrast, the Harvard architecture features separate memory spaces and distinct buses for instructions and data. This allows the CPU to fetch an instruction and access data concurrently, potentially leading to faster execution, especially in pipelined processors where multiple stages of instruction execution can proceed in parallel. Many modern CPUs, while conceptually Von Neumann, implement a modified Harvard architecture internally by using separate instruction and data caches to achieve simultaneous access, even if the main memory is unified.

● The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle: A High-Level Overview of Program Execution.

This cycle represents the fundamental, iterative process by which a Central Processing Unit (CPU) carries out a program's instructions. It is the rhythmic heartbeat of a computer.

1. Fetch: The CPU retrieves the next instruction that needs to be executed from main memory. The address of this instruction is held in a special CPU register called the Program Counter (PC). The instruction is then loaded into another CPU register, the Instruction Register (IR). The Control Unit (CU) orchestrates this transfer.

2. Decode: The Control Unit (CU) takes the instruction currently held in the Instruction Register (IR) and interprets its meaning. It deciphers the operation code (opcode) to understand what action is required (e.g., addition, data movement, conditional jump) and identifies the operands (the data or memory addresses that the instruction will operate on).

3. Execute: The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU), guided by the Control Unit, performs the actual operation specified by the decoded instruction. This could involve an arithmetic calculation, a logical comparison, a data shift, or a control flow change (like a jump). The result of the operation is produced.

4. Store (or Write-back): The result generated during the Execute phase is written back to a designated location. This might be another CPU register for immediate use, a specific memory location, or an output device. Simultaneously, the Program Counter (PC) is updated to point to the address of the next instruction to be fetched, typically by incrementing it, or by loading a new address if the executed instruction was a branch or jump. The cycle then repeats continuously for the duration of the program.

Youtube Videos

Key Concepts

-

A computer system consists of Hardware, Software, and Firmware working together.

-

Computer evolution progressed through generations marked by core technology changes (vacuum tubes -> transistors -> ICs -> microprocessors -> parallelism/AI).

-

The three core components of any general-purpose computer are the Processor (CPU), Memory, and Input/Output devices.

-

The Stored Program Concept is foundational, allowing programs and data to reside in unified memory.

-

Von Neumann uses a single shared bus; Harvard uses separate buses for instructions and data.

-

The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle is the continuous process by which the CPU executes instructions.