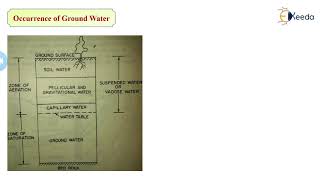

Occurrence of Groundwater

Enroll to start learning

You’ve not yet enrolled in this course. Please enroll for free to listen to audio lessons, classroom podcasts and take practice test.

Interactive Audio Lesson

Listen to a student-teacher conversation explaining the topic in a relatable way.

Introduction to Groundwater and the Hydrological Cycle

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Today, we will discuss how groundwater occurs, beginning with its origin from precipitation. This is a crucial part of the hydrological cycle, which sustains various ecosystems and supports human activities.

How does rainfall actually become groundwater?

Great question! Rainfall provides water that infiltrates into the soil. We call this process infiltration. Factors like soil texture and vegetation affect how much water gets absorbed.

What happens to the water after it infiltrates?

Once the water infiltrates, it percolates through the soil and rocks until it accumulates in underground formations, known as aquifers. Remember, infiltration leads to aquifer recharge!

I see! So, the type of soil affects how quickly this happens?

Exactly! Soil texture and structure are essential for determining infiltration rates. Let's keep this in mind as we explore the next concepts.

What other factors play a role in groundwater occurrence?

Good point! Other factors include land use patterns, slope gradients, and rainfall intensity. Each of these influences how efficiently water can infiltrate and recharge groundwater sources.

To sum up, groundwater begins with precipitation, which infiltrates the soil influenced by multiple factors! Remember the acronym 'SVE-R-L' to help you recall these factors: Soil texture, Vegetation, Terrain (slope), Recharge patterns, and Land use.

Zones of Subsurface Water

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Now, let's shift our focus to the zones of subsurface water. There are two primary zones: the Zone of Aeration, also known as the vadose zone, and the Zone of Saturation.

What is the difference between these two zones?

The Zone of Aeration is the area above the water table where pores contain air and some water that is not saturated. Contrastingly, the Zone of Saturation is below the water table, where all voids are filled with water—this is what we refer to as groundwater.

Is the water in the Zone of Aeration useful for anything?

Yes! The water in the Zone of Aeration, known as soil water, is crucial for plants and other life forms on the surface. It indicates the health of the ecosystem.

So how do we know where these zones are located?

Great question! The boundary between these zones is known as the water table. It can fluctuate based on factors like rainfall and land usage, so monitoring it is essential.

Can we remember the zones with anything?

Absolutely! A mnemonic like 'Air Above, Water Below' can help you remember the distinction: the ‘air’ represents the Zone of Aeration, while ‘water’ signifies the Zone of Saturation!

In summary, the Zone of Aeration holds unsaturated water, while the Zone of Saturation contains saturated groundwater. Keep in mind the mnemonic 'Air Above, Water Below'!

Rock Properties Affecting Groundwater Storage

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Let's dive into the properties of rocks and soil that affect groundwater. These include porosity, permeability, specific yield, and specific retention.

What does porosity mean?

Porosity is the ratio of the volume of voids to the total volume of rock. Higher porosity means more space for water storage.

And permeability? How is that different?

Permeability refers to the ability of the medium to allow water to flow through. Even with high porosity, if a material has low permeability, water won't move easily.

What about specific yield and specific retention?

Specific yield is the amount of water that can be drained by gravity, while specific retention is the water that remains due to capillary action. Remember: 'Yield is what you can use, Retention is what stays.'

That's a helpful way to remember it! How do these properties apply in real life?

In urban planning and agriculture, understanding these properties helps in managing groundwater effectively. For example, knowing the permeability of an area can dictate desalination or drainage efforts!

So, to sum up, porosity, permeability, specific yield, and retention are critical to understanding groundwater storage and movement. Use the phrase 'Yield is what you can use, Retention is what stays' for quick reference!

Introduction & Overview

Read summaries of the section's main ideas at different levels of detail.

Quick Overview

Standard

Groundwater originates from precipitation, which infiltrates the soil and percolates through rocks into aquifers. Understanding the zones of subsurface water and various rock properties is crucial for effective groundwater management.

Detailed

Occurrence of Groundwater

Groundwater plays a pivotal role in the hydrological cycle, emerging from rainwater that infiltrates the ground. The infiltration process is impacted by factors such as soil characteristics, vegetation, topography, and rainfall patterns. Subsurface water can be categorized into two main zones: the Zone of Aeration, which contains unsaturated water held by molecular forces, and the Zone of Saturation, where all voids are filled with groundwater. Key rock properties like porosity, permeability, specific yield, and retention significantly influence groundwater occurrence and movement. Understanding these concepts is essential for managing water resources sustainably.

Youtube Videos

Audio Book

Dive deep into the subject with an immersive audiobook experience.

Hydrological Cycle and Groundwater

Chapter 1 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

Groundwater originates from precipitation. A portion of rainfall infiltrates into the soil and percolates down through pores and fractures in rocks, accumulating in underground formations. The infiltration and recharge depend on:

• Soil texture and structure

• Vegetation cover

• Slope gradient

• Land use pattern

• Rainfall intensity and duration

Detailed Explanation

Groundwater is created when water from rain falls to the ground and seeps into the soil, moving downward through tiny spaces in the soil and rocks. This process is known as infiltration. Several factors determine how effectively this happens, including the type of soil (its texture), the plants that cover the land, how steep the ground is, how the land is used by humans (like for farming or building), and the amount and duration of rainfall. Each of these elements influences how much water can enter the ground and replenish groundwater supplies.

Examples & Analogies

Think of a sponge placed in a bowl of water. The sponge represents the soil, and the water represents rainfall. If you pour water into the bowl steadily, the sponge absorbs it up to a point. However, if the sponge is too compact or dirty, it won't absorb as much. Similarly, well-structured soil with good vegetation and gentle slopes allows more water to seep in and recharge the groundwater.

Zones of Subsurface Water

Chapter 2 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

Subsurface water is divided into two main zones:

1. Zone of Aeration (Vadose Zone):

• Lies between the land surface and the water table.

• Contains soil water, intermediate zone water, and capillary water.

• Water in this zone is not saturated and is held by molecular forces.

2. Zone of Saturation (Phreatic Zone):

• All pores and voids are filled with water.

• The top of this zone is known as the water table.

• Water here is called groundwater.

Detailed Explanation

Subsurface water exists in two key zones beneath the ground. The first is the Zone of Aeration. This is the upper layer, located between the land surface and the water table. Here, water fills spaces in the soil but does not saturate them completely; it exists alongside air and is referred to as soil water or capillary water. Below this is the Zone of Saturation, where all the spaces in the rocks and soil are completely filled with water. The boundary that separates these two zones is known as the water table, which indicates the top level of groundwater.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine a two-story sponge where the top layer is damp but not dripping with water, while the bottom layer is soaked and heavy with water. The damp top layer is similar to the Zone of Aeration, and the soaked bottom layer represents the Zone of Saturation. Water is plentiful in the soil below the water table, just as it is in the lower sponge layer.

Rock Properties Affecting Groundwater Storage

Chapter 3 of 3

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

The following properties of rocks and soil affect the occurrence and movement of groundwater:

• Porosity: Ratio of void volume to total volume of rock.

• Permeability: Ability of the medium to transmit water.

• Specific Yield: Volume of water that drains under gravity.

• Specific Retention: Water retained by capillary action.

Detailed Explanation

Several key properties of rock and soil significantly influence how groundwater is stored and moves through these materials. Porosity is the measure of how much empty space (voids) is present in the material compared to its total volume, which shows how much water it can hold. Permeability refers to how easily water can move through the material—high permeability means water flows easily, while low permeability means it does not. Specific yield describes the amount of water that can flow out of the soil or rock due to gravity, and specific retention refers to the amount of water that remains in the pores due to capillary forces, even when gravity isn't pulling it down.

Examples & Analogies

Consider a sponge again. A sponge with larger holes (a more porous sponge) can hold more liquid than one with smaller holes. If you place both in a bowl of water, the sponge with larger holes will soak up more water and drain it more quickly, illustrating the concepts of porosity and permeability. After lifting the sponge out of the water, you might notice it still holds some liquid inside (specific retention), which represents how certain soils retain water even when saturated.

Key Concepts

-

Groundwater Origin: Groundwater originates from precipitation that infiltrates into the soil.

-

Zones of Subsurface Water: The two main zones are the Zone of Aeration (unsaturated water) and the Zone of Saturation (saturated groundwater).

-

Rock Properties: Key properties like porosity and permeability affect groundwater storage and movement.

Examples & Applications

An example of a confined aquifer is a layer of water sandwiched between two impermeable rock layers, leading to high pressure.

The free flow of water in an unconfined aquifer allows for more dynamic recharge from surface rainwater.

Memory Aids

Interactive tools to help you remember key concepts

Rhymes

When it rains, groundwater gains, through soil it drains, to aquifers it reigns.

Stories

Imagine a thirsty tree that absorbs rainwater; it drinks deep from the soil, replenishing its roots while the water journeys below, filling underground lakes known as aquifers.

Memory Tools

To remember groundwater zones: 'A for Air (Zone of Aeration), W for Water (Zone of Saturation)'.

Acronyms

Remember 'R-P-D-S' for factors of recharge

Rainfall

Porosity

Drainage

and Soil structure.

Flash Cards

Glossary

- Aquifer

A geological formation that stores and transmits water in usable quantities.

- Recharge

Process through which groundwater is replenished by precipitation and infiltration.

- Porosity

The ratio of void volume to the total volume of a rock or soil.

- Permeability

The ability of a material to transmit water.

- Specific Yield

The volume of water that drains under gravity from a saturated rock or soil.

- Specific Retention

The volume of water retained by capillary action in a saturated rock or soil.

- Zone of Aeration

The layer of soil and rock above the water table that contains unsaturated water.

- Zone of Saturation

The substrate layer below the water table where all spaces are filled with water.

Reference links

Supplementary resources to enhance your learning experience.