Factors Influencing Rain Gauge Network Design

Enroll to start learning

You’ve not yet enrolled in this course. Please enroll for free to listen to audio lessons, classroom podcasts and take practice test.

Interactive Audio Lesson

Listen to a student-teacher conversation explaining the topic in a relatable way.

Importance of Topography

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Topography plays a vital role in the design of rain gauge networks. Can anyone tell me why?

Because mountains and hills can affect rainfall patterns!

Exactly! In mountainous regions, we need denser networks to account for orographic rainfall. Who can explain what orographic effects are?

It's when moist air is lifted over mountains, causing more rain on the windward side!

Great point! Let’s remember: denser gauges in varied terrain can capture more accurate data, especially due to elevation changes.

Is there a way to remember the importance of topography?

Absolutely! Remember the acronym 'HARD': Hills Require Additional Rain Gauges. This captures the need for density based on terrain!

Climatic Variability

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Now, let's explore climatic variability. Why do you think it’s crucial to consider this in network design?

Because areas with unpredictable rain need more gauges to capture all variations!

Exactly! In regions with high variability, we communicate the need for a gauge density that reflects those differences. Can anyone think of an example?

Tropical areas have intense rain events. More gauges help with accurate data, right?

Yes, good observation! Variability requires adequate geographic coverage to ensure no critical data is missed.

How can we remember that?

Think 'VARY': Variable Areas Require Yielding gauge coverage. It helps recall the need for density based on climatic unpredictability.

Purpose of the Study

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Let’s discuss why the purpose of a study is significant when designing a network.

Flood-related studies need precise gauges for accurate measurements!

Exactly! Flood forecasting demands a very detailed network. What happens if data is inaccurate?

You might miss critical events and increase risks!

Right! So, remember: 'Focused Data Drives Design'. It emphasizes that the purpose shapes how we set up our networks.

Does that apply to less critical studies too?

Yes! All study types benefit from clarity in design related to their needs. Well done on transforming concepts into actionable objectives!

Catchment Area Size Impact

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Now let’s look at the size of the catchment area. How does that impact our rain gauge network?

Larger catchment areas require more gauges to represent data accurately!

Exactly! Can you visualize why this is necessary?

Because if you have too few gauges, you risk missing rainfall in significant areas!

Correct! Remember the phrase ' SIZE: Sufficient Installation Yielding Zones', which highlights the need for adequate representation in larger areas.

That’s a helpful phrase!

Accessibility and Logistics

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Finally, let's examine accessibility and logistics. How might these considerations affect network design?

If it's hard to reach a location, it might be tough to maintain the gauges!

Precisely! Are there any other implications of accessibility?

Deployment issues and choosing less accurate locations due to difficulty!

That's right! Let’s hold onto the mnemonic: 'ALWAYS' — Accessibility Leads to Adequate Water Yielding surveillance. It reminds us that recognizing accessibility is critical!

Introduction & Overview

Read summaries of the section's main ideas at different levels of detail.

Quick Overview

Standard

Factors influencing rain gauge network design play a crucial role in achieving accurate rainfall measurements. Essential considerations include the region's topography, climatic variability, the purpose of the study, the catchment area's size, and logistical concerns regarding gauge accessibility and maintenance.

Detailed

Factors Influencing Rain Gauge Network Design

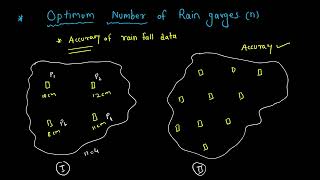

Designing an effective rain gauge network is vital for obtaining accurate rainfall data necessary for hydrologic studies and flood forecasting. Several factors must be taken into account during the design process:

- Topography: Regions with uneven or mountainous terrain require a denser gauge placement to capture the effects of orographic precipitation. This ensures that variations in rainfall due to elevation changes are adequately captured.

- Climatic Variability: Areas with significant rainfall variability, like tropical and temperate zones, necessitate a higher number of gauges. This helps in capturing localized rain events that could otherwise go unmeasured.

- Purpose of Study: Different studies have varying accuracy needs. For instance, flood studies require a more dense and strategically placed gauge network to ensure precise data for real-time forecasting.

- Size of Catchment Area: Larger areas demand a proportionally higher number of gauges to ensure representative data collection, minimizing the risk of missing significant precipitation events.

- Accessibility and Logistics: The practical aspects of gauge placement and ongoing maintenance affect where gauges can be installed. Areas that are hard to reach may limit accessibility, impacting how effectively the network can be maintained over time.

By considering these factors, a rain gauge network can be effectively designed to fulfill its intended goals in hydrologic observation and management.

Youtube Videos

Audio Book

Dive deep into the subject with an immersive audiobook experience.

Topography

Chapter 1 of 5

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

• Topography: Mountainous or hilly regions require denser networks due to orographic effects.

Detailed Explanation

Topography refers to the physical features of a landscape, such as hills, mountains, and valleys. In mountainous or hilly regions, the way rain falls can be greatly affected by these features. For example, when moist air flows over a mountain, it cools down, leading to precipitation on the windward side. This is called the orographic effect. To accurately measure rainfall in these varied elevations and changes, more rain gauges are needed to ensure that the data reflects the true variation in rainfall across different areas.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine you're trying to measure water collecting in different parts of a sloped garden. If the garden has a flat area and a hill, placing one measuring container on the flat area might miss how much water collects on the hill. Similarly, in rain gauge networks, more gauges are needed in hilly areas to capture the nuances of how rainfall is distributed.

Climatic Variability

Chapter 2 of 5

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

• Climatic variability: Regions with high rainfall variability need more gauges.

Detailed Explanation

Climatic variability refers to the differences in weather patterns that can occur in different regions. In areas where rainfall varies greatly from one location to another, a denser network of rain gauges is essential. This allows for a more detailed understanding of how rainfall differs not just over time, but also across space. The presence of multiple gauges helps in capturing these variations more accurately.

Examples & Analogies

Think of a classroom where students receive different amounts of rain from a sprinkler system due to varying distances from the source. To understand who gets more water, you would need to measure at different points across the room rather than just one spot. Similarly, in areas with varying rainfall, using more gauges ensures we don’t miss critical data.

Purpose of Study

Chapter 3 of 5

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

• Purpose of study: Flood studies demand higher accuracy and thus denser networks.

Detailed Explanation

The intended purpose of the rainfall data affects how many gauges are needed in a network. For instance, if the studies are focused on predicting floods, precision is crucial because even small errors in rainfall measurement can lead to significant consequences. Therefore, denser gauge networks are installed in areas where floods are a concern, ensuring that the data is as accurate as possible.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine organizing a fire drill at a school. If you only checked a few classrooms for safety measures, you might forget spots that could pose a risk. Instead, checking every room increases your chances of identifying issues. In the same way, a denser network in flood-prone areas ensures a comprehensive understanding of rainfall and its potential risks.

Size of Catchment Area

Chapter 4 of 5

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

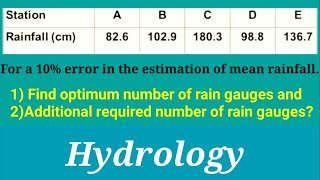

Chapter Content

• Size of catchment area: Larger areas require more gauges for adequate representation.

Detailed Explanation

The catchment area is the region from which rainfall is collected and where water drains into a particular point. Larger catchment areas need more rain gauges to provide an adequate representation of rainfall across the entire region. Without enough gauges, you risk missing important rainfall data from various parts of the catchment, which can lead to inaccurate assessments of water availability and potential flooding.

Examples & Analogies

Consider a large pizza divided into different slices. If you only take one sample from one slice, you might not get a good idea of what the entire pizza tastes like. Similarly, a larger catchment area requires several gauges to accurately capture the variability of rainfall throughout the whole area.

Accessibility and Logistics

Chapter 5 of 5

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

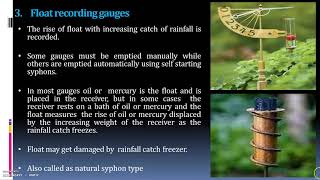

• Accessibility and logistics: Influence gauge placement and maintenance feasibility.

Detailed Explanation

When designing a rain gauge network, practical considerations like how easy it is to reach locations play a critical role. If a gauge is difficult to access, it may not be maintained properly. This can lead to malfunctioning equipment or data that isn’t current or reliable. Ensuring that gauges are placed in accessible locations improves their maintenance and the overall effectiveness of the network.

Examples & Analogies

Think about a gardener trying to water their plants. If the plants are in a reachable part of the garden, it's easier to water them regularly. However, if some plants are in a far corner that's hard to get to, they might not receive enough water. Similarly, rain gauges need to be placed where they can be easily checked and maintained to ensure they function correctly.

Key Concepts

-

Topography influences gauge density for accurate rainfall measurement.

-

Climatic variability requires higher densities due to unpredictable rainfall.

-

The study’s purpose shapes the overall design needs for accuracy.

-

Larger catchment areas necessitate a higher number of gauges.

-

Accessibility impacts gauge deployment and maintenance choices.

Examples & Applications

A mountainous region experiencing heavy rainfall on one side due to orographic effects needs a denser gauge network.

In a tropical area with frequent and intense rain variability, multiple gauges are necessary to capture all data points.

Memory Aids

Interactive tools to help you remember key concepts

Rhymes

If mountains rise and valleys lie, set the gauges near where rain does fly.

Stories

In the land of Tempest Valley, rain danced wildly over the hills, prompting the sages to hold a council. They decided that more rain gauges were necessary to capture each raindrop's tale, especially as storms swept in from the peaks.

Memory Tools

Use 'GAP' for Gauge Area Purpose: It reminds us to think about Density, Accessibility, and Purpose when designing.

Acronyms

HARD

Hills Require Additional Rain Gauges - to remember the need for denser networks in hilly regions.

Flash Cards

Glossary

- Topography

The arrangement and elevation of the physical features of an area.

- Orographic effects

Changes in rainfall patterns due to the elevation of terrain.

- Climatic variability

Diversity in weather conditions and rainfall patterns over time.

- Catchment area

The area of land where precipitation collects and drains into a common outlet.

- Accessibility

The ability to easily reach and maintain rain gauges in the network.

Reference links

Supplementary resources to enhance your learning experience.