Discovery of Electron

Enroll to start learning

You’ve not yet enrolled in this course. Please enroll for free to listen to audio lessons, classroom podcasts and take practice test.

Interactive Audio Lesson

Listen to a student-teacher conversation explaining the topic in a relatable way.

Introduction to Atomic Theory

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Alright class, who can tell me who first proposed the atomic theory and what it stated?

John Dalton proposed that atoms are the basic building blocks of matter that cannot be divided.

Exactly! Dalton's atomic theory was revolutionary, but what did it fail to account for?

It failed to account for the fact that atoms are made of smaller particles, like electrons.

Precisely! And this brings us to the exciting transitions in our understanding of atomic structure.

Experiments Leading to Electron Discovery

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Let's dive into how the electron was discovered. What do you know about cathode ray tubes?

They are tubes that have electrodes and are partially evacuated. When electricity is passed through them, it creates rays.

Correct! When Thomson conducted experiments with these tubes, what did he find?

He found that rays would move from the cathode to the anode and were affected by electric and magnetic fields.

Right! This led Thomson to conclude that these rays were composed of negatively charged particles, which we now call electrons. To remember this, think of 'Cathode rays carry negative charge' or CRNC.

Thomson’s Charge-to-Mass Ratio

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Now, focusing on how Thomson determined the charge-to-mass ratio, can anyone explain how he did this?

He balanced the effects of electric and magnetic fields to find where the electron would strike the screen.

Exactly! By measuring the deflection and knowing the strengths of the fields, he calculated the ratio, which was approximately 1.758820 × 10^11 C/kg. Let's use the mnemonic 'e/m ratio is substantial' to remember its importance.

That sounds helpful!

Millikan's Oil Drop Experiment

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

Next, we will talk about Millikan's experiment. What was the goal of the oil drop experiment?

It was designed to measure the charge on an electron.

Correct! By adjusting the electric field, he was able to calculate the charge on an electron to be approximately -1.6 × 10^-19 C. What acronym helps us remember that number?

We can use 'E for Electron = 1.6'.

Great mnemonic! This value represents fundamental constants that are critical in physics and chemistry.

Conclusion of Electron Discovery

🔒 Unlock Audio Lesson

Sign up and enroll to listen to this audio lesson

To wrap up today, how significant is the discovery of the electron in our understanding of atoms?

It changed our view of the atom completely, showing they are made of smaller particles!

Exactly! The discovery of the electron paved the way for advanced atomic models and a deeper understanding of atomic structure. Remember, 'Every atom isn't a single piece; it's a puzzle of particles!'

Introduction & Overview

Read summaries of the section's main ideas at different levels of detail.

Quick Overview

Standard

This section details the historical context of atomic theories leading to the discovery of the electron through cathode ray experiments, notably by J.J. Thomson. It highlights the significance of cathode rays, their characteristics, and the foundational experiments that paved the way for modern atomic theory.

Detailed

Detailed Summary

The discovery of the electron is a critical milestone in the history of chemistry and physics that fundamentally altered the understanding of atomic structure. Before the realization that electrons existed, atoms were thought to be indivisible units, as proposed by early philosophers and later by John Dalton in 1808. Dalton's atomic theory laid the groundwork for later exploration but did not account for the new evidence of particle physics.

The journey towards the discovery of the electron began with experiments on electrical discharge in gases. Michael Faraday's work in the 1830s laid a foundation by demonstrating the particulate nature of electricity when it passed through electrolytic solutions. Later, experiments conducted in cathode ray tubes by Thomson in the late 1800s led to critical insights.

The most significant experiment was Thomson's cathode ray tube experiment, where he showed that cathode rays—streams of particles emitted from the negative electrode (cathode)—were composed of negatively charged particles, which he named electrons. His measurements established a charge-to-mass ratio for electrons, confirming their existence as fundamental components of atoms. Additionally, Millikan's oil drop experiment provided precise measurements of the charge on the electron, further validating the findings of that era.

This discovery not only revolutionized atomic theory by introducing the idea of subatomic particles (electrons, protons, and neutrons) but also paved the way for various atomic models, including those proposed by Thomson and Rutherford, which attempted to describe the structure and behavior of atoms.

Youtube Videos

Audio Book

Dive deep into the subject with an immersive audiobook experience.

Faraday's Contribution

Chapter 1 of 4

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

In 1830, Michael Faraday showed that if electricity is passed through a solution of an electrolyte, chemical reactions occurred at the electrodes, which resulted in the liberation and deposition of matter at the electrodes. He formulated certain laws that suggested the particulate nature of electricity.

Detailed Explanation

Faraday's work highlighted that when an electric current passes through an electrolyte, it causes chemical changes. This was critical because it implied that electricity behaves like a particle rather than just a flow of energy. It suggested that there are discrete packets of charge, hinting that further research into the nature of these charges would be fruitful.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine you have a big swimming pool (representing the electrolyte), and every time someone jumps in (the electric current), they displace water, causing splashes depending on how they jump. Similarly, electric currents cause reactions that can be seen, indicating the presence of something more tangible than merely energy.

Cathode Ray Discharge Tubes

Chapter 2 of 4

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

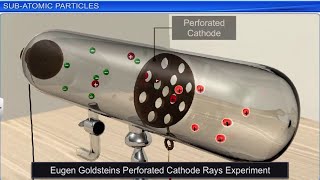

In the mid 1850s, many scientists, mainly Faraday, began to study electrical discharge in partially evacuated tubes, known as cathode ray discharge tubes. When sufficiently high voltage is applied across the electrodes, current starts flowing through a stream of particles moving in the tube from the negative electrode (cathode) to the positive electrode (anode). These were called cathode rays.

Detailed Explanation

Cathode ray tubes allowed scientists to visualize the behavior of electric currents in gases. When a voltage was applied, particles (later identified as electrons) emitted from the cathode traveled in straight lines towards the anode. Scientists could observe the effects of these particles hitting different materials within the tube, which led to further understanding of their properties.

Examples & Analogies

Think about a garden hose with water flowing through it; if you put your finger partially over the end, the water streams out in a certain direction. In a cathode ray tube, the applying voltage is like turning on the tap, and the electrons are akin to the water being pushed through the tube.

Observations from Cathode Rays

Chapter 3 of 4

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

The results of these experiments are summarized below: (i) The cathode rays start from cathode and move towards the anode. (ii) These rays themselves are not visible but their behavior can be observed with the help of certain kind of materials (fluorescent or phosphorescent). (iii) In absence of electrical or magnetic field, these rays travel in straight lines. (iv) In presence of electrical or magnetic field, the behavior of cathode rays is similar to that expected from negatively charged particles, suggesting that the rays consist of negatively charged particles, called electrons.

Detailed Explanation

These observations were key in identifying the nature of cathode rays. They not only revealed that cathode rays traveled in straight lines unless influenced by external forces but also confirmed the inherent negative charge of these particles—now known as electrons. This set the stage for understanding atomic structure and subatomic particles.

Examples & Analogies

It can be compared to how a magnet interacts with metal objects. If you were to throw some tiny metal filings into the air near a magnet, you’d see them align and move towards the magnet due to their opposite charges. Just like that, cathode rays are influenced by electric and magnetic fields, altering their paths and confirming their negative charge.

Conclusion on Electrons

Chapter 4 of 4

🔒 Unlock Audio Chapter

Sign up and enroll to access the full audio experience

Chapter Content

Thus, we can conclude that electrons are a basic constituent of all the atoms.

Detailed Explanation

The conclusion that electrons exist within all atoms was revolutionary. It shifted the view of the atom from being a simple sphere of matter to a complex structure with both positive and negative components, establishing a foundation for modern atomic theory.

Examples & Analogies

Imagine a chocolate chip cookie—where the dough represents the positive charge and the chocolate chips represent the electrons sprinkled throughout. This alteration from a basic structure to one with specific components reflects how our understanding of atoms evolved with the discovery of the electron.

Key Concepts

-

Cathode rays are streams of electrons emitted from a cathode.

-

The charge-to-mass ratio of the electron is a fundamental property.

-

Millikan's oil drop experiment provided the measured charge of the electron.

Examples & Applications

When Cathode rays are passed through a magnetic field, they bend, indicating their charge and mass properties.

Millikan's oil drop experiment confirmed electrons have a charge of approximately -1.6 × 10⁻¹⁹ C.

Memory Aids

Interactive tools to help you remember key concepts

Rhymes

Electrons in a tube, moving with glee, proves they're the charge, as clear as can be.

Stories

Once upon a time, a scientist named Thomson explored the depths of a tube where the electrons roamed. He found them whizzing with charge, paving the way for modern physics.

Memory Tools

C-R-E-A-M: Cathode rays emit all matter (C) of electrons, revealing their nature (R) and charge (E).

Acronyms

T.E.E. - Thomson's Electrons Examined in detail.

Flash Cards

Glossary

- Electron

A negatively charged subatomic particle found in all atoms.

- Cathode Ray Tube

A vacuum tube containing electrodes that shows the behavior of cathode rays when electricity is passed through.

- ChargetoMass Ratio

The ratio of the charge of a particle to its mass, important in identifying subatomic particles.

- Oil Drop Experiment

An experiment conducted by Robert Millikan to measure the charge of the electron using charged oil droplets.

Reference links

Supplementary resources to enhance your learning experience.